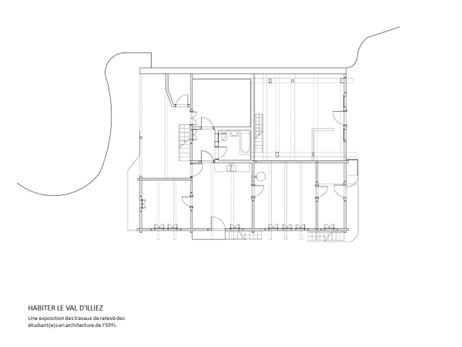

In our valley, the oldest dwellings were built to be ‘all in one’. Not only did the one roof shelter multiple generations of a family and their living quarters—the house also included cellars and attics for equipment, wood, and grain storage, as well as stables, barns, and a cacophony of farm animals!

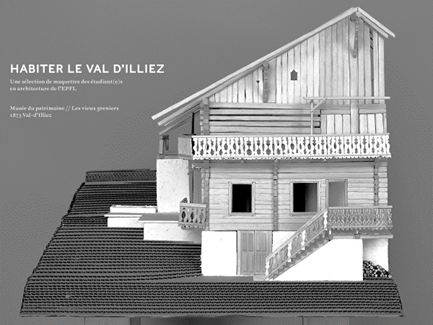

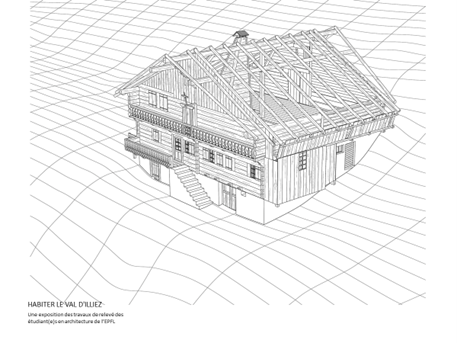

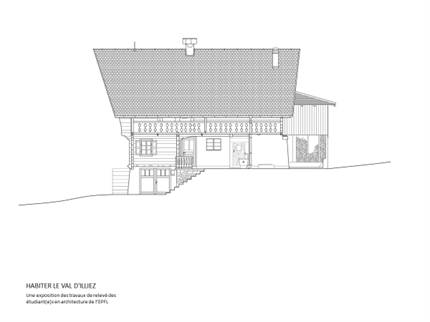

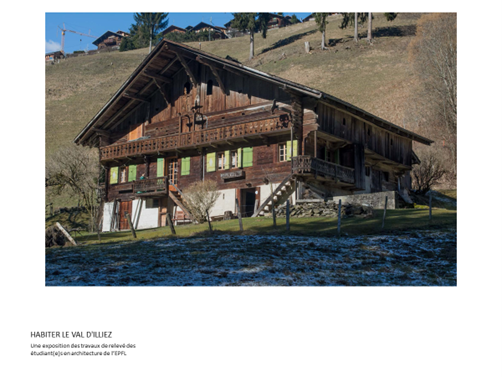

The lower floor was built of local stone, the main habitation was made of massive solid planks called madriers, and the gables (below the roof slope) were often made of reclaimed wood. It is exceedingly rare to find a chalet with its original gables, due to our harsh climate and damage caused by the violent winds, called Foehn, we experience at certain times of the year.

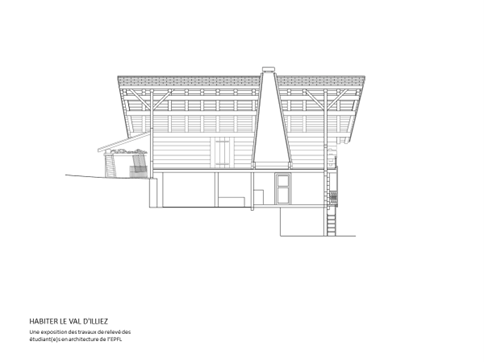

THE BELLOWS ROOFS

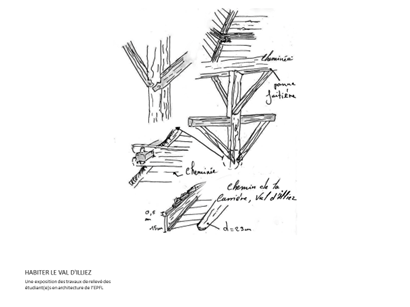

The toit en sifflet is one of the most remarkable feature of chalets in the Illiez Valley. From the ridgeline, the roofline cuts sharply back, making the chalets look like ships sailing through the alpine landscapes. The difference in surface can vary, anywhere from 8 to 13%. The vast space created under the eaves at the ridgeline helped provide better protection for the façade from the elements. Admittedly, our valley has a reputation for rather humid weather! At the same time, the backwards-slanting roofline allowed for more light to hit the windows. The point, which resembles a bellows, is more pronounced on the downhill side (the façade) of the chalet than the uphill side.

The balconies, referred to locally as ‘galleries’, were built with intricately carved balusters. In some cases, these carvings represented elements of the family coat of arms; in others a hobby. For example, balusters with a tulip were associated with the Mariétan family name. The symbolic shape was generally carved out of two baluster planks and only became visible once the balcony railing was assembled. Interestingly, not all balconies had the same design. Sometimes the three balconies had three different designs!

Another typical feature found on the old chalets is the ‘arm’, or the beam that supports the ridgepole. It was attached at an angle, between the façade of the chalet and the end of the ridgepole and engraved or painted on the visible side. In our valley, you can generally find elements like the construction date, a coat of arms, the initials of the first inhabitants, the sun, the moon, or a star.

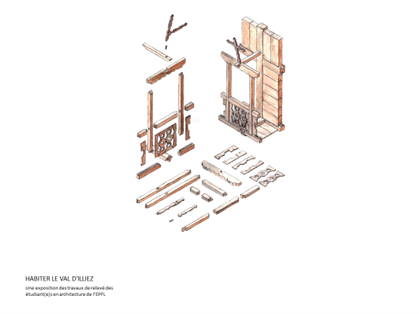

On each side of the frame, the beams that protrude from the facade are called chantignoles; they show the carpenter’s signature, usually represented by a personal design that he carved into each construction.

Under the eaves, on the slope side of the chalet, a ‘leaf gallery’ was often constructed with simple, sloping planks. There were two reasons for this: to dry the leaves collected in the forests in autumn to serve as bedding for livestock and to reduce wind exposure under the large surface of the roof slopes.

In the attic, there was a generally a massive vertical beam that supported the ridgepole. This was called the Om, or ‘man’; it was supported by the wall or main partition of the floor below, a partition which usually separated the family’s living quarters from the stable. This partition was not necessarily in the middle of the home.

The wooden chimney was called the borne. It was pyramidal in shape, and its construction remains a mystery even today! It is thought to have been built on the ground and then raised up and placed on a base independent of the chalet’s frame structure. It was built above the kitchen, where there was a woodshed, and smoke from the soapstone stove in the room was funneled through the chimney to smoke meat.

The wood used for these constructions was most often spruce for chalets in Val-d’Illiez and Champéry, and larch for buildings in Troistorrents. Geography dictates supplies and larch is rare above 800 m.

Illustrations from the ‘Living in Val-d’Illiez’ exhibition

Models of chalets made by architecture students from EPFL.